Overcoming the most common mistakes large organizations make when trying to shift to DevOps, Agile or modernize apps

John Ediger – DevOps & Agile Transformation Leader

As a DevOps & Agile transformation consultant, one of the most common questions I get is, “what have other companies struggled with in their transformation attempts such that we can learn from their mistakes?”

This has inspired me to describe a short list of what I have observed as the most common and problematic antipatterns of transformation and modernization attempts, along with how to overcome these tendencies.

The use of the term antipattern is defined in the paper as, “a commonly repeated pattern of action, process or structure that initially appears to be beneficial, but ultimately produces more bad consequences than beneficial results”. Each of these four are very common, and understandably tempting. Many IT leaders cut their teeth in a waterfall, plan-driven, and control-oriented world. It’s not their fault. An agile way of leading takes practice and learning but it also requires a bit of unlearning.

While the term “IT Transformation” is used widely and at varying levels, the scope used in this paper primarily involves efforts to radically improve business outcomes, speed, and agility by leveraging approaches such as Agile, DevOps, Cloud, and Applications Modernization.

Let’s first walk through the basic reasons that these four all too common antipatterns result in a failure to meet even the basic expectations of such transformations, and are often even detrimental to business outcomes.

- Modernize for modernization sake

We know that the majority of organizations today are contemplating or doing some sort of IT modernization and/or transformation. Most are in some state of agile transformation and are looking to modernize their IT capabilities. A 2018 survey1 by Statista showed only a measly 9% had not started to adopt DevOps or had no plans to do so. Everyone else is transforming or getting ready to. A rapidly growing number of organizations are pursuing cloud, shifting to microservices getting off mainframes or are engaging in app modernization projects.

There is nothing wrong with this of course. The problem arises when these are pursued simply to modernize without specific outcomes or goals. DevOps, for example, is a means to an end, not an end-state in itself. The same is true for cloud, app refactoring, mainframe migration and other app modernization endeavors. These are not easy undertakings and require a large commitment across the organization.

Likewise, agile transformations should be done with an intent to get specific benefits for the organization. Without this intent, results may not be commensurate with the very large effort of making the switch. With both DevOps and Agile, I’ve seen too many organizations stop short of realizing their expected large gains because they did not aim for specific outcomes.

The desired outcomes should also be realistic and match what DevOps and Agile actually are meant to do. Some leaders have misperceptions about what an agile transformation can accomplish. Just recently I was with a team who believed that agile will speed up code development and was trying to calculate what cost savings they can glean from an agile transformation. Groups such as these often shoot way too low. For example, rather than trying to get a 5% productivity gain from an IT department (which is not even the goal of agile in the first place), why not shoot for the larger gains that agile affords?

The true agile benefits are both more profound and more strategic. Organizations which holistically adopt agile are able to rapidly respond to changes in the environment, including market, technology, competition, and other forces. Another key benefit which dwarfs the benefits of solely focusing on the dev team efficiency is the ability to adjust plans quickly based on stakeholder feedback to get the right capabilities implemented to best meet the desired outcomes. Rather than meeting a set of established requirements, agile teams work to meet business outcomes. Instead of reducing their risk of not meeting a schedule, they reduce a bigger risk – the risk of not achieving desired results and outcomes with the right features.

As Mark Schwartz points out in his latest book, War and Peace and IT2, Microsoft found in a large study that among requirements, “only 1/3 of ideas actually accomplished their intended objective; another 1/3 actually had the opposite result, and 1/3 don’t have either effect”. This is where agile shines – not in meeting documented requirements faster, but in implementing less of the wrong features and more of the right features. The agile principle here is “maximizing the amount of work NOT done”. Now rather than a small IT development productivity gain, we’re talking about much larger and more impactful productivity gains for the business overall. But if an organization just sought after generic IT modernization by ‘doing agile” they may miss the greater gains and true power of “being agile”.

With a DevOps transformation effort, if the goal is simply to be “doing DevOps”, teams may reap some nice efficiencies or local optimization through the use of automation. But the biggest results come from targeting specific and measurable desired outcomes, and leveraging the pertinent DevOps practices and patterns to achieve those. Again, it’s not doing DevOps for DevOps sake, but meeting specific goals such as improved cycle time, measurable quality gains, and/or radical reductions in MTTR and change failure rates.

As DORA3-6 proved within their industry-wide studies, companies that made the most use of DevOps practices, with relentless focus on such specific measurable results, improved not just IT productivity, but company-wide results. These companies were 1.53 times as likely to meet or exceed their organization’s goals such as profitability, market share, units sold, and operating efficiency. They had 50% higher growth in market cap years7 over those companies that did not make this kind of deliberate and persistent use of DevOps practices. These organizations did not achieve these results by generically modernizing just because it was the latest and greatest IT trend.

2. Big Bang Transformation

Another very common IT Transformation and Modernization anti-pattern that I have observed is where organizations attempt very large “big-bang” transformations. We know these add significant risk and rarely work. Regardless, they are still often attempted, and as a result can set organizations back further than had they never even tried the transformation in the first place.

This is well documented by many of the today’s leading IT thought leaders. Jez Humble, Joanne Molesky & Barry O’Reilly in 2015, provided a good overview of the risks of this phenomenon in their book, Lean Enterprise8 (in my opinion a must read for all technology and business executives and leaders). They show the humorous and all-to-familiar graph of organizations oscillating between “business as usual” and “change program” with a repeated sliding back to their previous state. Beyond a big bang transformation being unsuccessful, it has the larger risk of reducing the appetite of leaders to attempt such a change again, citing that “we tried that, it didn’t work” or “see, I knew such a change was overrated … or not worth it”.

The ultimate irony is when leaders use a big-bang, plan-driven, waterfall approach when the transformation itself is to move off waterfall (to go agile and adopt DevOps). Sounds crazy, but I see this all the time – going agile in a waterfall manner?! (I even see this within service provider and consulting firms). The basis of agile is to be able to adjust plans and requirements based on learnings from incremental implementation and feedback loops. This is a perfect fit for transformations especially because of the inevitable issues, roadblocks, and cultural inertia which can only be discovered through actual implementation attempts. An agile approach allows for quick and flexible adjustments to the discovered roadblocks and constraints. The misconception by many waterfall-minded leaders is that a strict and detailed roll-out plan provides more control and less risk. Nothing could be further from the truth. In fact the opposite is true. For anyone with doubts about this, I recommend reading Mark Schwartz’s prior book, A Seat at the Table9, which provides a compelling (and humorous) view of risk, planning, requirements, governance, and transformation – all from an agile leadership vs. a waterfall-based perspective.

The other problems with Big Bang transformations is that they tend to run long and yield results predominantly at the end of the transformation. Given the rapid pace of IT advances and changes, this often leads to the necessity of starting a new transformation again as soon as the initial transformation has completed. The recommended pattern here is to do continuous transformation and use an agile approach. You get results as you go and you have flexibility to continuously adjust as the IT landscape changes. Risk is reduced through transforming in small increments and making adjustments and removing impediments based on learning from the actions taken. Lower risk, more control, more predictability, and more results! This is the antidote for the Big Bang transformation anti pattern. Agile at its finest.

3. One-size-fits-all adoption

This third antipattern of one-size-fits-all adoption I see most prominently with DevOps transformation efforts, but is also common with shifts to cloud, micro services, and several other transformation and modernization attempts.

Here’s how this anti pattern plays out for DevOps adoption. An organization has some local successes with a couple teams, but they struggle to scale adoption broadly. Using the approach well known by management for decades, they mandate “adoption” and create a status tracking mechanism measuring that every team adopts the tools and becomes “compliant” or “converted” to DevOps.

The problem with this is multifaceted. First, it rarely yield results (more on this in anti pattern #4). Second, DevOps is by definition a continuously improving endeavor, not something you finish, become compliant with or convert to. Third, and the part most often missed, is that DevOps includes a myriad of principles, practices, patterns and tools which can and should be applied selectively and in order of priority dependent upon the specific needs, goals, current state and challenges of each particular app or value stream. Sure there are a few common tools and some common organizational DevOps patterns which may make sense to universally apply, but this is the exception, not the rule.

Let’s illustrate this by taking three actual simple examples (abbreviated case studies) of different value streams, as shown in the following table:

and recommended DevOps starting points based on Value Stream Mapping

There are endless examples, with apps of all types: COTS apps, mainframe apps, SAP apps, mobile apps, legacy apps, SaaS apps, apps in maintenance mode, mission critical apps, etc. DevOps principles of fast flow, amplification of feedback loops, and continuous improvement/experimentation apply to all of these. They all can make use of well-established DevOps/Agile/Lean patterns and practices such as continuous integration, everything in version control, shift left continuous testing, service virtualization, infrastructure-as-code, and combining dev, test and support engineering. These are just a few of many dozen of DevOps options. The trick is to NOT assume all value streams within one organization have the same current state, goals, needs and challenges and NOT to treat DevOps adoption as something that all teams must obediently comply to and ‘check the box’. Unless of course the organization just wants to claim that they have “completed” a DevOps or Agile transformation, but they are not really interested in the results.

There is also a very important human factor with avoiding the one-size-fits-all anti-pattern. I’ve heard Gary Gruver, an early DevOps transformation pioneer from HP (where I cut my teeth), tell this story multiple times. You mandate to a skeptical team manager to implement DevOps, claiming it will dramatically improve their speed and quality. They reluctantly comply, get limited results and say, “see, it did not really work”.

On the other hand, if you hold them accountable to specific speed and quality objectives, provide them a framework of a set of Agile and DevOps principles, practices and patterns, (along with coaching and training support) and let them determine the best way to achieve those results, teams will own the results and accomplish objectives much more effectively than any mandated checklist.

The one mandate I do recommend that all executives make, is for the team to adopt a disciplined continuous improvement and transformation process (aka DevOps Kaizen). By setting the business objectives, and driving the continuous improvement process, executives will see much better transformation results than by mandating a one-size-fits-all checklist.

4.Technology and Tools only focus

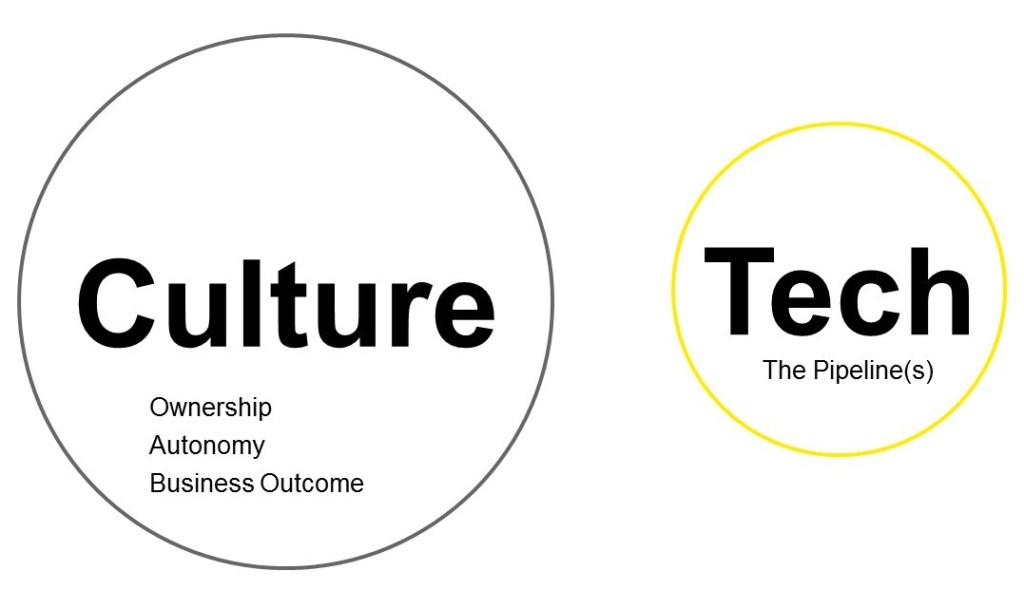

This is the grandfather of transformation anti-patterns. Intellectually, I believe most understand this – the fact that tools are the 20% and the 80% is about how teams work (culture, leadership, practices, principles, and mindset). But when it comes to actual priority, emphasis and steps taken within transformation efforts, I see the majority of organizations expecting transformations to DevOps, Agile, Cloud, etc. be successful simply by rolling out tools, methodologies and lifecycle processes.

I have run countless DevOps/Agile leadership workshops and seminars talking about critical success factors in transformation where I emphasize this critical 80/20 rule. Heads nod in agreement and understanding. Then the questions start — the majority of them are about tools.

The tools are the easiest part of the equation, while the culture change is more challenging and more difficult to measure. It’s no wonder that this is often over-looked as part of transformation efforts, but focusing only on the 20% (the tools) will at best get 20% of the benefits.

Numerous companies have asked for help and advice about how to scale DevOps adoption. They have experienced pockets of success with a few small unicorn teams but are struggling with scaling beyond that. They explain how they have provided and mandated a common toolchain. But they are not seeing widespread adoption or they are not getting expected results. Tools alone are not the answer.

The critical success factors for DevOps mostly center on how teams work. This includes continually adopting rapid feedback loops, continuously optimizing end-to-end flow, continual improvement through hypotheses and experimentation, ownership of outcomes, collaboration, eliminating silos, automation, shifting left, empowering teams, etc. Tools play an important role here but the tools are not the solution. DevOps is not a set of tools, or the “onboarding” of tools. Not even close.

A classic example is Jez Humble’s famous three questions10 where he asks an audience to raise their hands if they are “doing continuous integration”, which is one of many DevOps practices. All those using CI tools, like Jenkins and doing automated builds and automated testing typically raise their hands. He proceeds to have people keep their hands up only if “1) all the engineers pushing their code into trunk / master (not feature branches) on a daily basis, 2) every commit triggers a run of unit tests, and 3) when the build is broken, it is typically fixed within 10 minutes?” The hands successively drop and by the end, there are very few really doing CI, and hence really getting expected results. But the leadership team has rolled out the tools and the teams have “adopted” them. A similar antipattern exists with Agile. Teams roll out agile by adopting not only the tool, but all the important ceremonies, such as with scrum, for example. These are essential initial steps, but they don’t mean that these organizations are reaping sweeping benefits. Agility is about much more than methodology. As described in anti-pattern #1, many of these teams “do agile” but are not “being agile”. They may go through the motions, using the tools and the methodology, but without truly incorporating the agile principles, continuously improving, and adopting agile end-to-end across functions (especially across leadership, governance, and business), results tend to be minimal. Local optimization when adopting agile is a very common variation of this antipattern, sometime referred to as water-scrum-fall.

Antidote to the leading transformation antipatterns

Given these four primary transformation antipatterns …

- Modernizing for modernization sake,

- Big-bang transformation,

- One-size fits all adoption,

- Technology & Tool dominant focus,

… what is the antidote? What are the best ways to prevent and avoid these traps?

The first step is to understand and recognize these patterns when they happen. Seems obvious, but waterfall ways of thinking are ingrained, and organizations are often unaware of the underlying mindset, culture and paradigm by which they are operating. In addition, we need to replace these with proven principles, disciplined implementation methods and known successful transformation patterns.

Recommendation include:

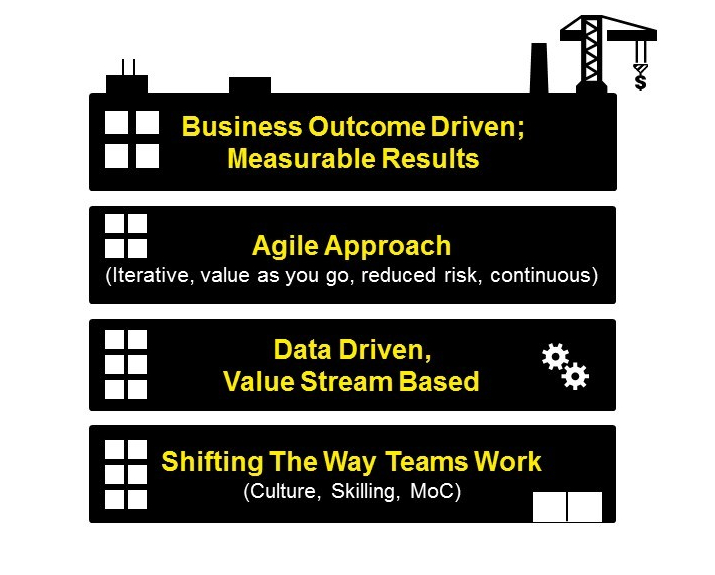

- Think of transformation as a continuous process that never ends rather than one big transformation or even a set of large projects

- Use tried and true agile principles and

practices for transformation, just as a team would for agile product

development or maintenance, such as:

- prioritized epic backlogs

- hypothesis and action-driven rather than plan-driven

- incremental results focus

- doing small improvements followed by quick assessment and adjustments

- Use a data driven approach, whereby transformation efforts are applied to value streams based on their specific outcome goals and challenges. Adopt Value Stream Mapping (the right way).

- Align leadership at all levels to support,

encourage, and model a culture of continuous improvement where teams are

empowered and accountable to measurable value stream goals. This involves

- sponsoring and tracking goals and kaizen iterations

- addressing org-wide impediments

- empowering teams

- helping the organization fundamentally “get good at getting better”

- Create an enablement team of coaches, rather than a heavy governance and/or compliance team, such as a traditional PMO

- Partner with a Service Provider who applies these principles and approaches into their consulting, enablement, and delivery offerings. This partnership helps an organization become self-sufficient in their continuous transformation and modernization efforts.

There are two core threads common to all these principles and patterns which are critical success factors:

- Leadership & Culture

- A system or framework for continuous transformation.

First, leadership culture change is paramount. This culture shift requires multiple ingredients (too many to embellish upon in this paper), but these include a burning platform, a clear vision, and continuous development of executives, leaders and practitioners. A good transformation consultant is highly recommended to help with this. As DORA11 has also demonstrated, culture can also be influenced and changed through consistent application of practices, such as Continuous Delivery. In other words, the adoption of technical practices from the bottom up can actually shift the broader organization culture.

The development of leaders and practitioners cannot be underestimated. The DevOps and Agile practices and tools have minimal impact without all levels of the organization understanding and embracing a body of knowledge of principles core philosophies which have revolutionized both IT and business. These include but are not limited to the Agile Manifesto, Systems Thinking, DevOps-Lean Product Development, which entail elements such as Value Stream Management, Three Ways of DevOps, Kaizen, Minimal Viable Product, and Lean-Agile leadership. This may sound like a lot, but these principles are the underpinnings of the absolute best way of developing and managing systems today. These are proven science which continue to evolve and improve. They are not fads or trends, and should be considered mandatory elements of the continuous learning and development curricula by leaders and practitioners alike.

As part of successful continuous transformations, leaders must understand, support, and apply Lean, DevOps and Agile principles and practices.

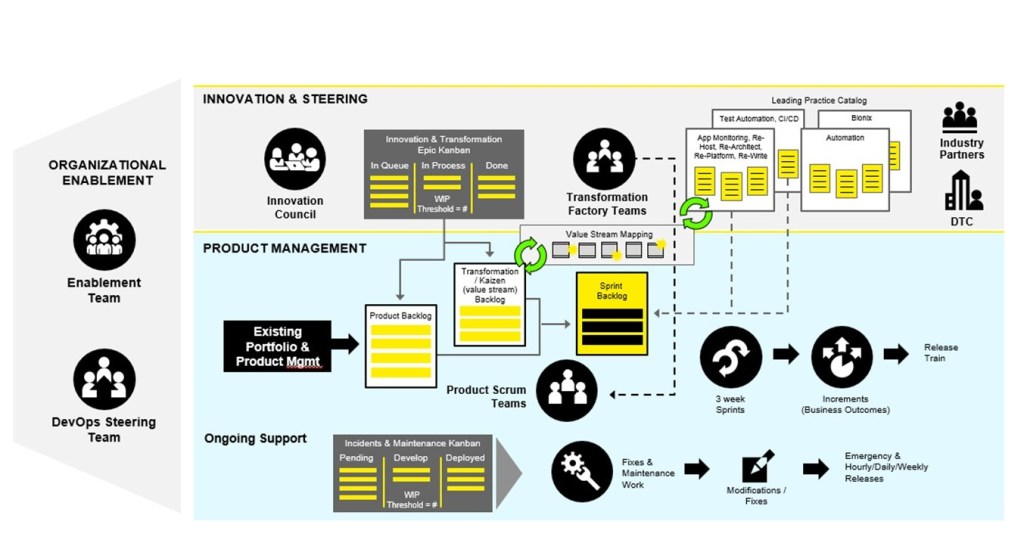

The second core thread is a system or framework for continuous transformation. Think of this as a continuous transformation factory building upon all the principles listed above. It has a lightweight leadership prioritization mechanism using an epic-level Agile Kanban construct to make transformation work visible and limit WIP (work in process). It’s analogous to a lightweight Portfolio SAFe framework but for transformation rather than solution development. It leverages Value Stream Mapping and assessments to form lower level prioritized backlogs of transformation epics and stories. And transformation work is done in sprints with rapid feedback cycles and adjustments, all aimed at business outcomes and measureable results. A model of this continuous transformation factory framework is depicted below.

The emphasis of the Factory is to achieve measurable business results based on the specific value stream goals. The teams leverage multiple modernization disciplines (e.g. agile, DevOps, app modernization, automation, and cloud native adoption) in a small-batch prioritized backlog manner. Rather than approach one of these at a time across the enterprise, these are evaluated as a single set of possible countermeasures and transformation implementations to be applied based on the business needs and improvement goals of the individual value streams.

This is the ultimate antidote to the typical transformation shortcomings due to the all-too-common antipatterns described in this paper. More details and case studies will follow as evolutions and various customized versions of it are currently being applied successfully across multiple companies. Stay tuned.

Best of luck in your continuous transformation journey and remember to steer clear of those pesky antipatterns!

Notes:

- https://www.statista.com/statistics/673505/worldwide-software-development-survey-devops-adoption/

- Schwartz, War and Peace and IT (Portland, OR: IT Revolution, 2019)

- https://cloudplatformonline.com/2018-state-of-devops.html

- https://puppet.com/resources/whitepaper/2015-state-devops-report

- https://puppet.com/resources/whitepaper/2016-state-of-devops-report

- https://puppet.com/resources/whitepaper/2017-state-of-devops-report

- Forsgren, Humble, and Kim, Accelerate, (Portland, OR: IT Revolution, 2018), 212

- Humble, Molesky, O’Reilly, Lean Enterprise, (Sebastopol, CA: O’Reilly Media, Inc., 2015)

- Schwartz, A Seat at the Table (Portland, OR: IT Revolution, 2017)

- Fowler, Martin, Continuous Integration Certification, https://martinfowler.com/bliki/ContinuousIntegrationCertification.html

- Forsgren, Humble, and Kim, Accelerate, (Portland, OR: IT Revolution, 2018), 56-57,87-88